Hastings Commons transforms derelict buildings into community assets

Don’t Waste Buildings organised a tour and roundtable discussion with a community-led regeneration project in Hastings that has raised nearly £34 million from 133 different funding sources since 2014, demonstrating an innovative model for transforming abandoned buildings while keeping neighbourhoods alive.

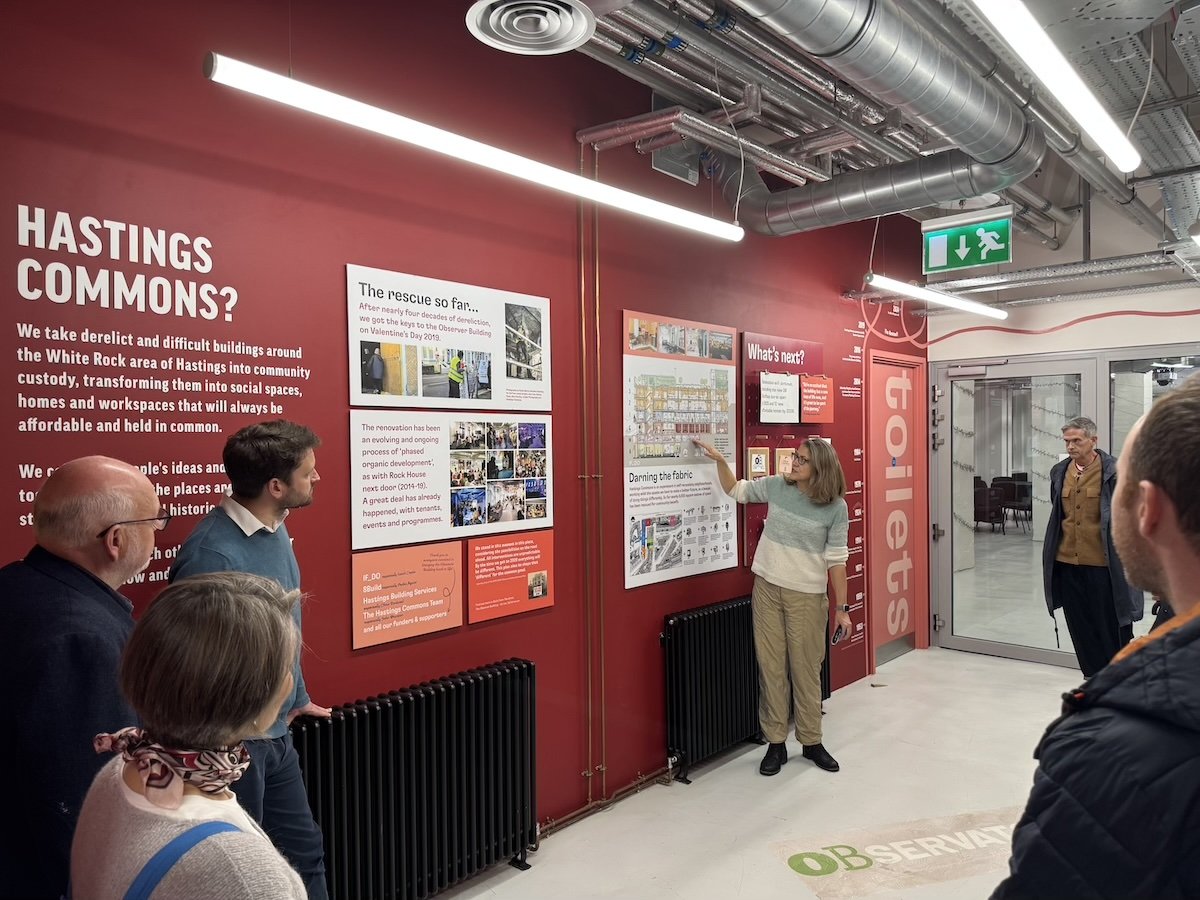

In a small 150-meter radius neighbourhood on the edge of Hastings' town centre, an experiment in community-led development is quietly revolutionising how derelict buildings can be brought back to life. The Hastings Commons project has become a beacon for sustainable construction, proving that retrofitting existing structures can deliver both environmental benefits and lasting social impact.

Since 2014, the project has secured nearly £34 million through a complex web of 133 grants and loans – a testament to both the scale of funding needed for community regeneration and the ingenuity required to make it work. The achievement becomes even more remarkable considering the project operates through four separate but intertwined legal entities, carefully designed to balance risk while accessing diverse funding streams.

A Complex Structure

The project's organizational structure includes a social enterprise property company, a registered charity, a housing association, and a community land trust – each serving distinct purposes while preserving different organisational cultures. This complexity allows access to funding sources that wouldn't be available to a single entity, while managing both social and financial risks.

"We're focused on 'darning the fabric' of neighbourhoods rather than demolition and rebuild," explains Dr Jess Steele OBE, who leads the project. "It's about patient capital and long-term steady state rather than rapid financial return."

This patient approach has paid dividends in community stability. Despite market rent increases since 2019, Hastings Commons has maintained stable rents across its properties, supporting its core mission of preventing displacement and maintaining community cohesion. The model prioritises local agency and incremental impact over rapid development cycles typical of larger regeneration projects.

Environmental and Social Returns

The environmental benefits of the retrofit-first approach are substantial. By renovating existing buildings rather than demolishing and rebuilding, the project reduces embodied carbon emissions by 50-75% compared to new construction. This tackles a significant but often overlooked source of carbon emissions – the energy embedded in construction materials and building processes.

But the social returns may be even more impressive. The project runs a youth council with a 17-year-old president and integrates youth training directly into governance structures. This isn't just community engagement theatre – it's a deliberate strategy to build local leadership skills aligned with long-term regeneration goals.

"Youth engagement is broad and inclusive, focused on creating a safe space and building trust before deeper involvement," notes Steele.

Proving the Model Works

The Hastings approach has involved significant personal and organisational risk, particularly in early stages, with leadership taking their own financial risks to prove the model works. This evolving approach contrasts sharply with typical large-scale regeneration projects that often prioritise speed over community input.

The project is now developing a comprehensive case study library to capture its economic, social, and environmental impacts. Translating social outcomes into measurable indicators, such as apprenticeships and jobs created, are important, though softer benefits like youth development and community cohesion remain challenging to quantify.

The model challenges both gentrification and dereliction by offering an alternative rooted in social regeneration or what Steele calls ‘self-renovating neighbourhoods’ (this was the subject of her PhD thesis completed in 2022).

Scaling the Approach

The success in Hastings is attracting attention from policymakers and investors, as well as internationally, looking for replicable models. The project's tight geographical focus maximises both social impact and operational manageability, creating a blueprint that other communities might adapt to their own contexts.

As the project collects post-occupancy evaluations and embodied carbon data from completed buildings, it is building empirical evidence for the broader benefits of community-led retrofit. The data will support arguments for policy changes that could unlock similar projects nationwide.

The Hastings Commons model demonstrates that with creative financing, patient capital, and deep community engagement, derelict buildings can become engines of environmental sustainability, economic growth and social regeneration – proving that small-scale, community-led development can deliver outsized impact.